If the brain goes hungry, Twinkies look a lot better, a study led by researchers at Yale University and the University of Southern California has found.

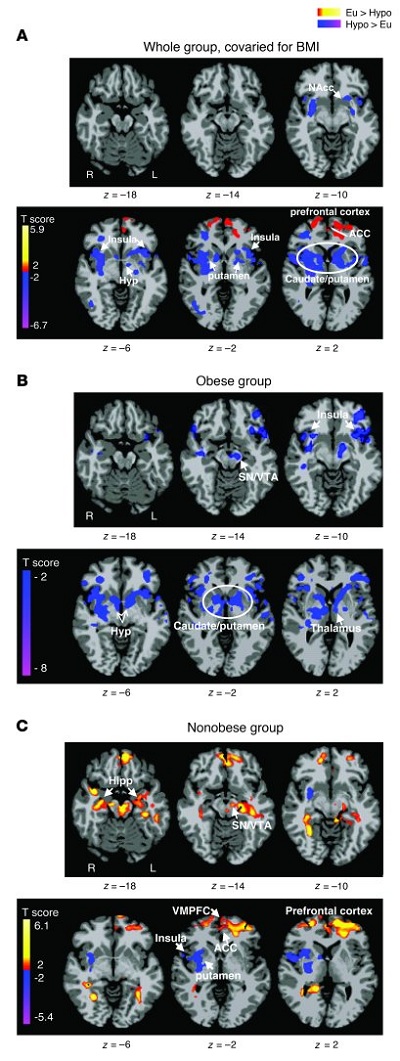

Brain imaging scans show that when glucose levels drop, an area of the brain known to regulate emotions and impulses loses the ability to dampen desire for high-calorie food, according to the study published online September 19 in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

“Our prefrontal cortex is a sucker for glucose,” said Rajita Sinha, the Foundations Fund Professor of Psychiatry, and professor in the Department of Neurobiology and the Yale Child Study Center, one of the senior authors of the research.

The Yale team manipulated glucose levels intravenously and monitored changes in blood sugar levels while subjects were shown pictures of high-calorie food, low-calorie food and non-food as they underwent fMRI scans.

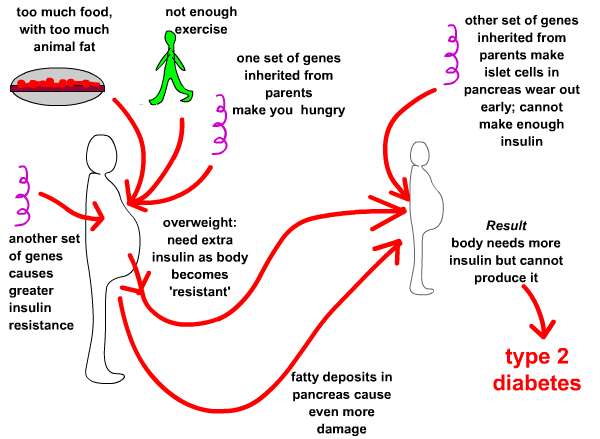

When glucose levels drop, an area of the brain called the hypothalamus senses the change. Other regions called the insula and striatum associated with reward are activated, inducing a desire to eat, the study found. The most pronounced reaction to reduced glucose levels was seen in the prefrontal cortex. When glucose is lowered, the prefrontal cortex seemed to lose its ability to put the brakes upon increasingly urgent signals to eat generated in the striatum. This weakened response was particularly striking in the obese when shown high-calorie foods.

“This response was quite specific and more dramatic in the presence of high-calorie foods,” Sinha said.

“Our results suggest that obese individuals may have a limited ability to inhibit the impulsive drive to eat, especially when glucose levels drop below normal,” commented Kathleen Page, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Southern California and one of the lead authors of the paper.

A similarly robust response to high-calorie food was also seen in the striatum, which became hyperactive when glucose was reduced. However, the levels of the stress hormone cortisol seemed to play a more significant role than glucose in activating the brain’s reward centers, note the researchers. Sinha suggests that the stress associated with glucose drops may play a key role in activating the striatum.

“The key seems to be eating healthy foods that maintain glucose levels,” Sinha said. “The brain needs its food.”

Obesity is a worldwide epidemic resulting in part from the ubiquity of high-calorie foods and food images. Whether obese and nonobese individuals regulate their desire to consume high-calorie foods differently is not clear. We set out to investigate the hypothesis that circulating levels of glucose, the primary fuel source for the brain, influence brain regions that regulate the motivation to consume high-calorie foods. Using functional MRI (fMRI) combined with a stepped hyperinsulinemic euglycemic-hypoglycemic clamp and behavioral measures of interest in food, we have shown here that mild hypoglycemia preferentially activates limbic-striatal brain regions in response to food cues to produce a greater desire for high-calorie foods. In contrast, euglycemia preferentially activated the medial prefrontal cortex and resulted in less interest in food stimuli. Indeed, higher circulating glucose levels predicted greater medial prefrontal cortex activation, and this response was absent in obese subjects. These findings demonstrate that circulating glucose modulates neural stimulatory and inhibitory control over food motivation and suggest that this glucose-linked restraining influence is lost in obesity. Strategies that temper postprandial reductions in glucose levels might reduce the risk of overeating, particularly in environments inundated with visual cues of high-calorie foods.

It is common knowledge in running endurance training (e.g. marathon training) that you need to maintain blood glucose levels in order to avoid “negative thoughts” from the brain. Thoughts that will persuade you to stop running.

So, why should this be any different throughout the day or evening when we are not stressing our bodies?

Interesting how obesity plays a role, where an obese person sort of loses their way with regulating their desires for high calorie food.